The Microbiologist – Working on a NASA-CSA project was a dream come true – and 13 years on, I’ve traveled the world unraveling the secret of contemporary microbialites.

I wandered into my mentor’s office for our first official meeting after taking a Ph.D. position at the University of British Columbia to inquire about potential projects. My mentor informed me that we are looking for a student to work on a NASA-CSA project named MARS-Life.

While I had been fascinated by space since childhood due to my love of Sci-Fi literature, including The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury in 1950, and being an immense original Star Trek fan, working on a NASA project was a dream come true.

“Have you ever heard of stromatolites?” my adviser said. I immediately said “No,” but afterward clarified, “You mean the rock formations in caves?”

My mentor said ‘No,’ then added, “These are microbialites, which are these particular types of microbial mats that over time transform into stone” – and these turned out to be part of the NASA-CSA project.

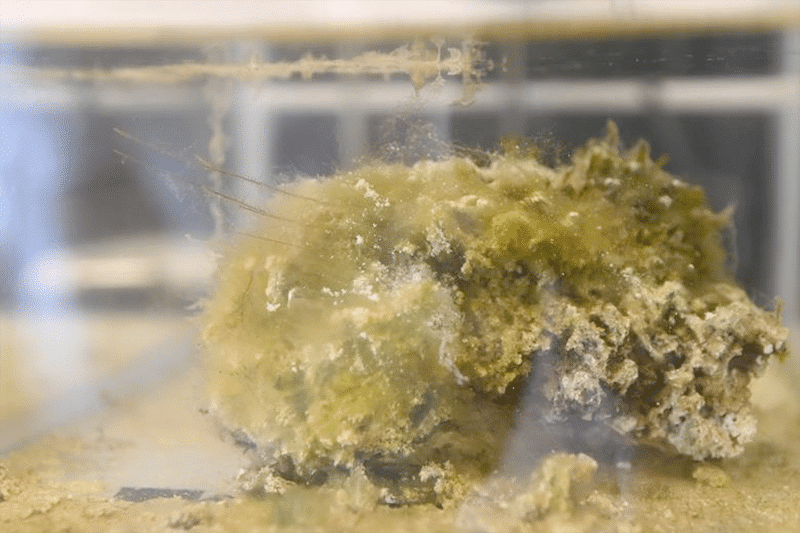

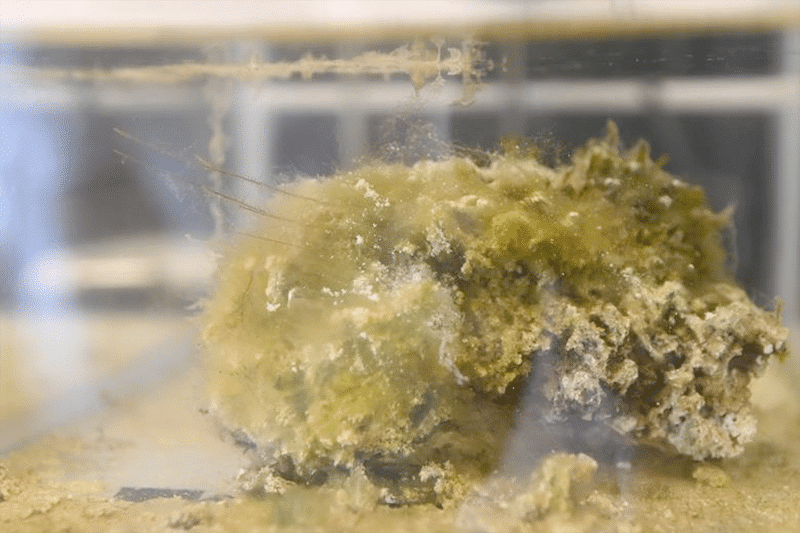

Source: Richard Allen White III, Modern microbialite from Greenlake, NY (near Syracuse NY)

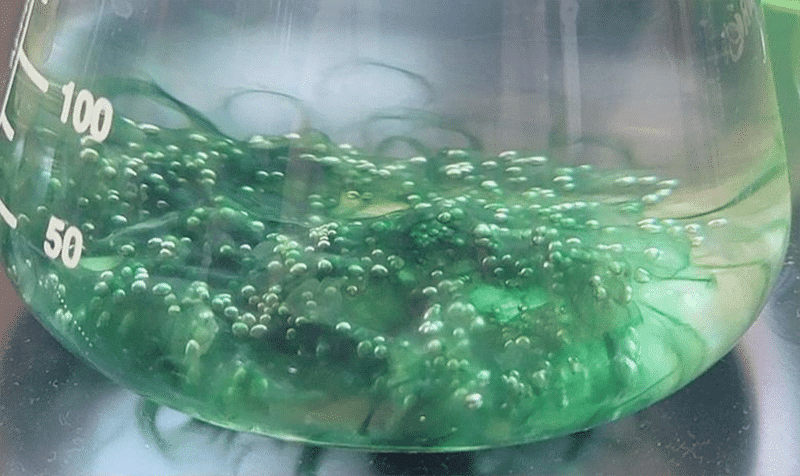

I’ve worked on contemporary microbialites all around the world since then. Shark Bay, Australia; numerous places in Mexico (including Cenote Azul and Bacalar); Pavilion and Kelly Lake in British Columbia; and Clinton Creek in the Yukon Territory, Canada.

My work includes metagenomic efforts in Clinton Creek, Pavilion Lake, and Shark Bay to enumerate microbes, their viruses, and the accompanying expected microbial metabolisms.

I never imagined that I would travel all over the world to study these structures, that I would keep them like pets in my lab, that they would be important for educating future scientists, and that they would still contain secrets to our fundamental knowledge of the biosphere and its biogenesis.

What Is a Microbialite?

Microbialites are carbonate organosedimentary deposits generated by microbial communities. They are classified based on their physical and geological characteristics, with two main groups: internally laminated (a fine layer at least 1 mm thick) and unlaminated (no layers).

Stromatolites (i.e., Greek strôma meaning ‘layer’), which are laminated layered carbonates but non-spherical; oncolites, which are both layered and spherical; and leiolites, which have amorphous internal structures, are examples of laminated microbialites. The most prevalent unlaminated thrombolites (i.e., Greek thrómbos meaning ‘clot’), which feature irregular clot carbonate structures, and dendrolites (i.e., Greek déndron meaning ‘tree’), branched carbonate projections that appear like tree branches, are among the unlaminated.